Tuesday, November 6, 2018

This is part 4 of my 18th century stays project.

Continued from: Inserting Boning, Seaming, and Grommets

Now comes the most dreaded part of making stays. I used leather for comfort and durability reasons, and even though chamois is thin, it’s still leather. And I hate hand sewing. My fingers agree. It does have one advantage, though, which is that it has some flexibility to work around curves, much like bias tape. Leather also has no raw edges to fray.

Full disclosure: my sewing machine (a Juki DDL 8500-7) is capable of sewing right through cable ties, even the thick type, with a sharp needle. Despite its appearance, it’s actually designed for mid-weight fabrics, not heavy duty applications like leather. Your machine may not be able to do this, or it may require a bit of manual help on the wheel. Do not try to backstitch through a cable tie; every time I accidentally did, I broke a needle. So, with that precaution, try it on some scraps and see if you can. If not, you’ll need to do the whole binding process by hand or leave all the bones 1/4 inch short so they don’t extend into the binding.

Methods

So, how do we make this a less aggravating experience? Well, the answer depends on what you’re trying to accomplish. If you’re making a historical reproduction, it’s time to get acquainted with your needle, thread, and thimble. I’m not; this is for 21st century daily wear, and nobody but me should be seeing it anyway! ;-) What follows is what I learned.

[Read more…]

This is part 3 of my 18th century stays project.

Continued from: Fabric and Boning Channels

Inserting Boning, Part 1

I inserting boning in two stages to make the job easier and to allow me to be more precise. The first stage is for bones which will have both ends of their channels closed off by seams, rather than binding. The only occurrences of this are the horizontal bust bones, since one end butts against a full length bone and the other against a seam.

Cutting Boning

For the 75 pound cable ties, you can just use a pair of stout and sharp scissors. For the 175 pound duct ties, you’ll probably damage your scissors, so use a pair of diagonal cutters, making sure to point the end that will be cut off into a garbage can. It will go flying at a high rate of speed. If I didn’t already wear decently large eyeglasses, I’d totally be wearing safety glasses. Seriously. Pointy plastic in the eye has never been fun for anybody.

Boning End Preparation

Once you cut it to length (with the correct angle on each end), you’ll want to slightly round the end so that it isn’t going to damage your fabric or binding. I did this in two stages. First, use scissors to slightly clip the corners, just enough to take off the point. Second, hold the end near a candle flame until the edges just start to soften and round over. This may take some practice, but it’s far easier than using sandpaper. Note: If you over-melt the plastic, it will become bubbly and brittle, which you don’t want. If that happens, get a new piece and start over. Plastic is cheap.

The final length should allow you to insert the bone into the channel and have it flush or just below flush with the end of the channel, which is defined either by the edge of the fabric or a seam allowance line. Better to err on the side of being too short rather than sticking out; a 1/16 inch isn’t going to make much of a difference if too short, but will if too long. To get this right, I fully prepare one end, insert it into the channel, mark the length with a pencil (on the smooth side, which should be facing towards the outside fabric), remove it from the channel, cut it, and prepare the second end. You’ll probably get more than one bone per cable tie since a lot of the bones are short.

Seaming and Lining

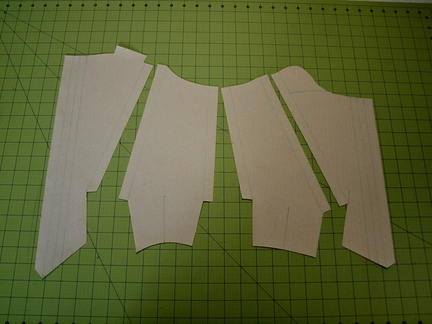

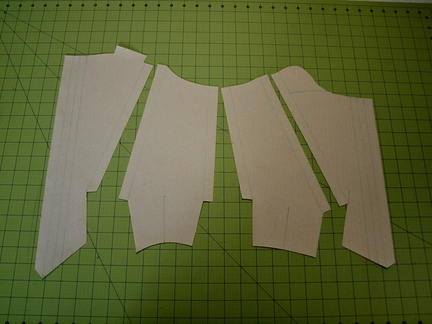

Seam the four pieces per side together and press the seam allowances open, making sure not to overheat any bones you’ve already inserted. It will look like this.

[Read more…]

This is part 2 of my 18th century stays project.

Continued from: Introduction and Materials

Prepare and Cut Fabric

Tip: starching your fabric before cutting will make this whole project much easier, since it won’t be stretching on you. You’re trying to get a bunch of layers to match up and look nice and you’re doing a lot more sewing than typical for a lined garment. And, yes, always pre-wash your fabric. Run it through a couple of cycles on hot water and hot dry. You want any shrinkage to happen now, before you spend days cutting and sewing.

Cutting it out was easy with a rotary cutter. Just take your time and be precise.

Mark Seam Allowances

Go ahead and mark your seam allowances, so that you know how much space you have to work with. You’ll notice that I’ve pre-marked one large boning channel inside of the grommet line on the back and one small channel on the front. Since they are needed, no matter the rest of the boning layout, I drew them in with the seam allowances. For the reason for these channels, read below under My Approach. You’ll also want to transfer the bust line stitching line to the coutil for later use. Any cutting lines (like for tabs) I marked with a pencil.

[Read more…]

Monday, November 5, 2018

In May of this year, Taryn and I vacationed in Virginia as a combined trip for her brother Dan’s wedding and a two-year wedding anniversary trip for us. Two of our stops after the wedding were Mount Vernon and Colonial Williamsburg, where Taryn fell in love with the women’s clothing. We grilled the interpretive staff at both locations to understand construction details and style considerations. I’ve never sewn women’s clothes before, let alone from two and a half centuries ago, so I had plenty to learn!

The basic working clothing for a woman would have been the shift, stays, petticoat, short gown, kerchief, apron, and cap. Taryn wanted to have a petticoat and short gown outfit of her own for everyday wear. Now, the challenge with this is that the outfit only looks “right” with the stays underneath to shape the bust correctly. So, not only am I learning to make women’s garments, but jumping straight to the challenge of corsetry! This project turned out to not be all that difficult, but it did take a lot of time. From cutting to completion, it was one month of work. Now, granted, I have a day job that involves no sewing, but I did probably spend a couple of evenings a week and most Saturdays and a couple of Fridays on this project.

Some background on stays (and why Taryn isn’t as crazy as you might think): Unlike Victorian era corsets, which were laced so tight that they shifted the bones around and deformed internal organs, 18th century stays conform to the torso and support the breasts. One of the interpreters commented that they act more as a reminder to keep proper posture (upright rather than slouching) and proper ergonomics (squat rather than bent over) when picking things up. Spoiler alert: Taryn says it’s far more comfortable than any bra she’s ever worn, even her expensive, good bras. Thinking about it, that makes sense; instead of elastic pulling the breasts in tight and thin straps transferring the load to the shoulders, the entire torso carries the load, distributed by the body-shaped bones.

One interpreter recommended we take a look at the Simplicity 8162 pattern by American Duchess, as it’s a fairly accurate modern pattern for 18th century stays. I needed modern instructions for my first attempt, as well as sizing I could trust. You’ll also notice that I’ve used, almost exclusively, modern techniques. I love my sewing machine and I don’t love hand sewing. These will be used for everyday wear, not for reenacting, so I’m not worried about it looking 100 percent historically correct.

Oh, and the stays versus corset terminology? It depends on the time period. Stays tend to come earlier usage than corset, but both words were used at this time period (1790s). I’ll use stays for these instructions, but Taryn usually refers to them as her corset. And technically, it’s a pair of stays. Anyway, off of the boring terminology and on to the fun part, making ‘em!

Materials

- Coutil - It’s worth buying the real stuff, available from multiple sellers on Etsy, so that your finished product doesn’t twist into weird shapes. It’s also a joy to work with.

- Outer fabric - I used quilting cotton, but I’d pick something stronger next time for durability.

- Lining fabric - I used the same quilting cotton as the outer fabric, which was fine for the lining.

- Boning - I used a combination of 36 inch duct ties (175 pound tensile strength) from Home Depot and 18 inch cable ties (75 pound tensile strength) from Amazon.

- Grommets - I used 5mm grommets from Kam Snaps (you’ll also need the tools to install). Note that to be period correct, you’d need to hand stitch the eyelets rather than use metal grommets.

- Twill tape - 1/2 inch wide, as called for on the pattern. Once again, Etsy is your friend when trying to find natural colored cotton twill tape.

- Chamois - I used this instead of twill tape for the binding, both for comfort and durability. Available from your local auto parts store in the car cleaning section. Just make sure it’s actual leather and not a synthetic imitation.

Make a Mock-Up

Being the cautious person that I am, I cut out the pattern pieces for the size that the pattern envelope called for based on Taryn’s measurements and make a quick mockup from cotton duck I had lying around. No bones, no grommets, just stitched together to get an idea of whether we were even close. I’ve heard that taping some bones to the fabric can help get a better idea of how it works; I’ll probably try that in the future. The mockup looked tolerably close, even though it looked terrible without any structure from bones, so I proceeded with cutting out the real fabric.

Next: Preparing and cutting fabric, and marking and sewing boning channels.